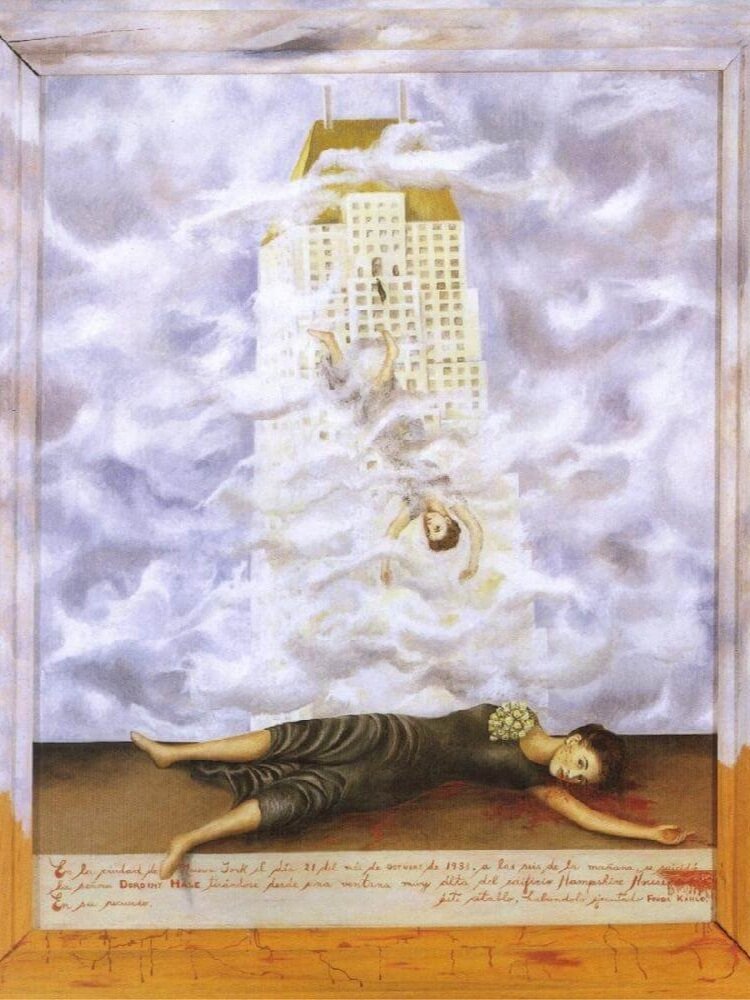

Jitterbugging (1939)

Marion Wolcott is known for her candid documentary photographs taken for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during America’s Great Depression. Joining Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and other photographers who produced iconic images for the FSA, Wolcott documented America’s staggering wealth inequalities, its race relations, the poverty and deprivation experienced during the Depression, and the benefits to the population of federal subsidies and programs. “As an FSA documentary photographer, I was committed to changing the attitudes of people by familiarizing America with the plight of the underprivileged, especially in rural America,” she once said. Along with images of coal miners, farmers harvesting tobacco fields, and affluent spectators at the races, Wolcott also captured moments of transcendence, such as in Jitterbugging (1939), an iconic image of African-Americans dancing in a club.

Marion Post was born in New Jersey on June 7, 1910. After her parents’ divorce, she was sent to boarding school and spent summers and holidays with her mother in Greenwich Village. She met many artists and musician during her time in The Village and later studied at The New School.

Post trained as a teacher, and went to work in a small town in Massachusetts. There she saw the reality of the Depression and the problems of the poor. When the school closed, she went to Vienna to visit her sister. While there, she witnessed Nazi attacks on the Jewish population and soon after returned to America for safety. She resumed teaching, continued her photography, and became involved in the anti-fascist movement. At the New York Photo League, she met Ralph Steiner and Paul Strand who encouraged her. When Steiner learned that the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin kept sending her to do ‘ladies' stories, he presented her portfolio to Roy Stryker, head of the Farm Security Administration. Stryker was impressed by her work and hired her immediately.

In 1941, she met Leon Oliver Wolcott, deputy director of war relations for the U. S. Department of Agriculture under Franklin Roosevelt. They married, and Marion Post Wolcott continued her assignments for the FSA, but resigned shortly thereafter in February 1942. Wolcott found it difficult to fit in her photography around raising a family and a great deal of traveling and living overseas.

In the 1970s, a renewed interest in Wolcott's images among scholars rekindled her own interest in photography. In 1978, Wolcott mounted her first solo exhibition in California, and by the 1980s the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art began to collect her photographs. The first monograph on Marion Post Wolcott's work was published in 1983.

Marion Post Wolcott died November 24, 1990.